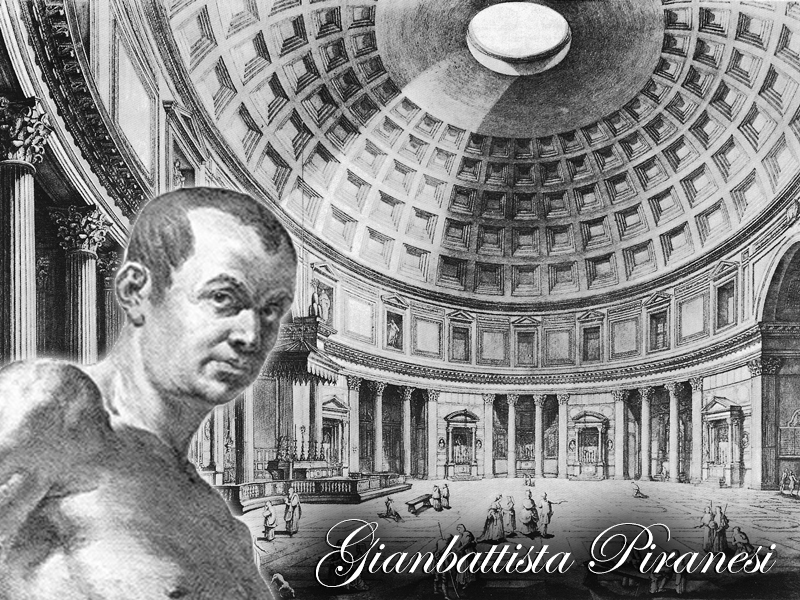

Giovan Battista Piranesi

Biography of Giovan Battista Piranesi

Giovan Battista Piranesi (1720-1778) was a famous Italian engraver, architect and antiquarian, best known for his engravings of Roman architectural views and antiquities.

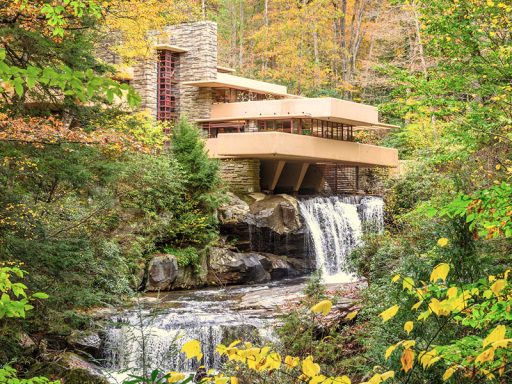

In Rome, Piranesi became passionate about ancient ruins and classical architecture. He began to devote himself to engraving, producing a series of views of Rome and its antiquities. His most famous work is the series of engravings entitled “Le Vedute di Roma” (Views of Rome), which contributed greatly to spreading interest in Roman antiquity in Europe.

Piranesi was notable for his detailed and imaginative style, which often emphasized the grandeur and magnificence of ruins. Over the course of his career, he also produced a series of prison engravings, known as the “Imaginary Prisons”, which displayed intricate and imaginative architectural environments.

Giovan Battista Piranesi died in Rome on 9 November 1778. His legacy lives on through his graphic works, which continue to be admired and studied for their artistic beauty and historical importance in documenting architecture and antiquity Roman.

1720

4 October: born to Angelo and Laura Lucchesi in Mojano di Mestre. 1735 – 40

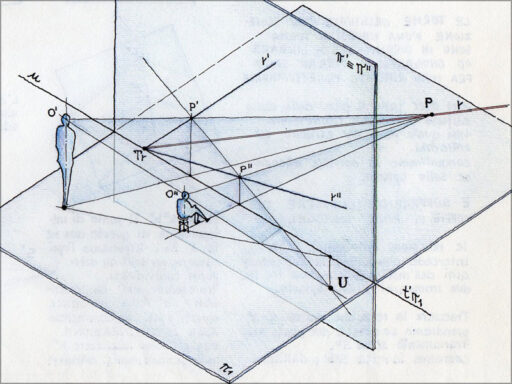

He studies with his uncle Matteo Lucchesi, architecture with Giovanni Scalfurotto, perspective and engraving with Carlo Zucchi. From his brother Angelo, a Carthusian monk, he learned Roman and Latin history.

1740

He leaves for Rome, as a draftsman, following the new Ambassador of Venice, Francesco Venier.

1741

He begins to engrave the small views for Roman publishers.

1741-43

He attended the studio of the engraver Giuseppe Vasi.

1743

First part of Architectures, and perspectives invented, and engraved by

Gio. Batta. Piranesi Venetian Architect dedicated to Mr. Nicola Giobbe.

1743 – 44

In the workshop of G.B. Tiepolo (?). In Venice he has some small decoration assignments, it is believed.

1744

Plan of the Corso del Tevere (with Carlo Nolli). Performs the Caprices.

1744 – 46

G. Wagner’s agent in Rome: he installed himself on the Corso, in front of the French Academy.

1745

Capric invention of etching prisons brought to light by Giovani Buzard Roma Mercante al Corso.

1745 – 1778

Views of Rome.

1748

It brings together in the “Various views of ancient and modern Rome designed and carved by famous authors” by the bookseller Fausto Amidei, the already engraved Vedutins (47 tables out of 94).

Roman Antiquities of the Times of the Republic, and of the first Emperors, designed and engraved by Giambattista Piranesi Venetian Architect.

Map of Rome in the edition of G.B. Nolli.

1749

P.L. Ghezzi makes a caricature of him (D2).

1750

G. Polanzani engraves the portrait of G.B. Piranesi (DL).

1750

Various Works of Architecture Grotesque Perspectives Antiquity on the taste of the ancient Romans invented and engraved by Giambattista Piranesi Venetian Architect collected by Giovanni Bouchard Mercante Librajo al Corso in Rome 1750.

Various views of ancient and modern Rome designed and carved by famous authors; new edition (39 tables out of 79 by Piranesi).

c. 1750/51

Sepulchral chambers of the ancient Romans which exist in and out of Rome.

1751

The Magnificences of Rome (34 Views of Rome) published by Giovanni Bouchard.

1752

Collection of various views of both ancient and modern Rome, mostly carved by the famous Giambattista Piranesi and other engravers. Bookseller G. Bouchard (47 tables out of 96 by Piranesi).

He marries Angela Pasquini, who appears to have been the daughter of Prince Corsini’s gardener. He uses the dowry to buy the copper plates for the engravings of the Roman Antiquities.

1753

Trophies of Octavian Augustus Raised for the victory at Actium and conquest of Egypt With various other ornaments diligently obtained from the most precious remains of the ancient factories of Rome useful to Painters, Sculptors and Architects … They are sold in Rome by Giovanni Bouchard Mercante Libraio sul Corso a S. Marcello in Rome. 1753.

1755

Daughter Laura is born. Meet Robert Adam.

1756

Roman Antiquities. Work of Giambattista Piranesi Architect. Venetian (4 volumes).

1757

He is elected honorary member of the London Antiques Society (D11) on 24 February.

1757

Letters of justification written to Milord Charlemont and to him agents of Rome by Mr Piranesi, Partner of the royal society of antiqùarj of London. Around the dedication of his work of Roman antiquities made to the same lord and lately suppressed.

1758

Benedict XIV dies on May 3. On 6 July the Venetian Carlo Rezzonico was elected and took the name of Clement XIII.

1758 o 1759

Francesco Piranesi is born

1760-61

Prisons of invention by G: Battista Piranesi Archit. Veins. At the author in Strada Felice near the Trinità dei Monti. 2nd edition.

1761

2 February: he is appointed Academician of S. Luca.

From spring he settled in Palazzo Tomati, Strada Felice (now Via Sistina) near Trinità dei Monti.

1761

From this year he began to distribute single sheet engravings, which he entitled «Catalog of the works brought to light so far by Gio. Batt. Piranesi ». In the sheet he lists his production which he will continue to update in subsequent re-editions.

Of the Magnificence and Architecture of the Romans: Work of Gio. Battista Piranesi, member of the Royal Academy of Antiquaries in London. The Ruins of the castle of the Acqua Giulia located in Rome near S. Eusebio and falsely called the Acqua Marcia with the declaration of one of the famous passages of the Frontinian commentary .., by Gio Battista Piranesi. They are sold by the author at Trinità de ‘Monti, in Rome 1761 in the printing house of Generoso Salomoni.

1762

He gets extensive help from Pope Rezzonico for his publications.

J.B Piranesii Lapides Capitolini sive Fasti Consulares triumphalesque Romanorum ab urbe condita … with a dedication to Clement XIII. The Campo Marzio of ancient Rome by G.B. Piranesi partner of the royal society of antiques dealers in London with a dedication to Robert Adam. Description and drawing of the Emissary of Lake Albano by Giovanni Battista Piranesi.

Two caverns decorated by the ancients on the shore of Lake Albano.

1763

Visit Chiusi and Corneto.

Accurate and succinct topographical description of the Antiquity of Rome by Abbot Ridolfino Venuti Cortonese. In Rome 1763.

1764

Antichità d’Albano c by Castcl Gandolfo Described and engraved by Giovambattista Piranesi in Rome 1764. Frontispiece with dedication to Clement XIII.

Blackfriars Bridge.

4 plates for “The Works in Architecture” by R. and J. Adam published in 1779. Collection of some drawings by Barberi da Cento known as il Guercino. In Rome 1764.

He receives the task of restoring and renovating the apse and the choir of S. Giovanni in Laterano. He carries out the drawings and the project, but not the work. Cardinal G.B. Rezzonico commissions him to restore S. Maria del Priorato on the Aventine.

1764 c.

Antiquities of Cora described and engraved by Giovanni Battista Piranesi.

1765

Remarks by Gio. Battista Piranesi on the letters of M. Mariette aux auteurs de la Gazette Litteraire de L’Europe, inserted in the Supplement of the same Journal printed on Sunday 4 November 1764 and Opinion on architecture, with a Preface and a new Treaty of Introduction and Progress of Fine Arts in Europe in Ancient Times.

1765 dopo

Some Views of Triumphal Arches, and other Monuments Raised by Romans … designed and engraved by Cavalier Gio Batista Piranesi. (Roman Antiquities of 1748 with new title).

1766

Accurate and succinct topographical and historical description of modern Rome. Posthumous work of Abbot Ridolfino Venuti Cortonese. Printed by Carlo Barbiellini (many editions up to 1802 and 1824). In October the work of S. Maria del Priorato (D19) ends. On 20 October Clement XIII visits the completed works.

1767

He works in the apartment of Cardinal Rezzonico at the Quirinale.

He is appointed by the pope, Knight of the Golden Speron. He draws and portrays the remains of Hadrian’s Villa in Tivoli several times.

1769

Different ways of adorning the paths and every other part of the buildings derived from Egyptian, Etruscan, and Greek architecture with an Apologetic Reasoning in defense of Egyptian Architecture, and Tuscany Work of the Cavalier Giambattista Piranesi Architect. Dedication to Cardinal G.B. Rezzonico.

Pope Clement XIII dies

1770

From this year he will continue to visit Pompeii and Herculaneum.

1772

He enters into controversy with the Academy of S. Luca for the monument to be dedicated to Pio Balestra.

1773

Trophy O Sia Magnificent Coclide Marble Column Composed of large boulders where the two Dacian wars made by Trajan are sculpted in the middle of the great forum erected to the same emperor by order of the senate and Roman people after his triumphs, all designed by Apollodorus. .. Dedication to Pope Clement XIV.

1775/6 c.

Antonine Column.

1777

Visit and draw the temples of Pesto: these are his latest drawings.

1778

Map of Rome and Campo Marzio.

Vases Candelabra Cippi Sarcophagi Tripodi Luceme and ancient ornaments designed and engraved by cav. Gio. Batt. Piranesi published in the year 1778.

Different views of the remains of three large buildings still visible from the ancient city of Pesto, otherwise Posidonia, located in Lucania.

He is unable to engrave all the tables of the Views of Pesto: his son Francesco will help him complete them.

G.B. Piranesi died on November 9 in his home in Rome. The funeral will take place in S. Andrea delle Fratte where he is provisionally interred while waiting to be permanently buried in the tomb prepared for him by the Rezzonico in S. Maria del Priorato on the Aventine.

The family commissions the sculptor Giuseppe Angelini to sculpt the statue.

1779

The work “The Works in Architecture” by R and J. Adam is published in London. It contains four plates that had been engraved by Piranesi, based on a design by Robert Adam, in 1764.

From this year onwards the activity of chalcography continues: the sons Francesco and Laura continue to engrave. Pietro follows and controls the sales.

1792

The general catalog of his works is published.

1799

Due to political reasons, Francesco and Pietro emigrated to Paris, where they continue the activity of chalcography.

1800

Francesco and Pietro reprint the works of their father. Legrand prepares a manuscript which was to be introduced to the works.

1810

Francesco dies.

1835 – 39

The Firmin-Didot house buys the engraved branches and publishes the works of Piranesi.

1839

Pope Gregory XVI decided, through Cardinal Antonio Tosti, to purchase all the branches of the Piranesi Chalcography, which thus returned definitively to Rome.

On this occasion, at least a brief mention of the first Venetian dates is permitted. On the life of Piranesi we have two fixed points. The birth in Mojano di Mestre, according to Canova’s indication (reported here in the Documentation at the Dl) and the baptism (here to the God) in the Venetian church of S. Moisé, on November 8

Alessandro BETTAGNO (written)

1720. The deed marks the 4th of October as the date of birth. The problem of the place is not of great importance. Mojano di Mestre is a locality not far from Venice, marked on the topographic maps of the time and corresponds to the territory to the right of the “Terraglio”, the road that leads from Mestre to Treviso, at the height of the current municipality of Mogliano, today in province of Treviso. A.H. Mayor hypothesized the possibility that his father was with his family on the mainland engaged – as a construction manager, as he really was – in some important construction: and this would explain better than all the uncertainty of the documents on the place of birth. Another problem of Venetian dates is given by the departure and return to the lagoons and therefore serves to specify the young artist’s first stay in Rome. Legrand, a very often reliable biographer having been familiar with Francesco Piranesi and his family both in Rome and in Paris, refers to the favorable opportunity of a new ambassador who was to be sent to Rome and the young artist was thus introduced in the sequel as “Draftsman”: meeting his strong desire to visit the city that was at the height of his thoughts. This opportunity must have been offered by the appointment of Francesco Venier who was called to replace the much better known Marco Foscarini, future doge and always exchanged as the protector of Piranesi; which seems to me at odds with reality, as Ambassador Foscarini was now at the end of his mandate. Francesco Venier, on the other hand, has been in Rome since October 1740 and, from the same city, still signs a dispatch of his in December 1743. It therefore seems to me that, better than many suppositions, the dates of stay of the Venetian ambassador specify his presence in Rome by the young Piranesi. These dates, on the other hand, are confirmed in the letter of dedication to Nicola Giobbe of 18 July 1743, where he spawns the saying when speaking of his stay in Rome: “… the third year is being completed”. At this point it seems probable to me that he would return to Venice together with Ambassador Venier in the winter of 1743-44. Another sure point of his biography is, in fact, constituted by the letter that the artist sends from Venice to Mons. Giovanni Bottari, the librarian of the Corsini princes, sent on 29 May 1744 (here D22).

After this date there is no other link between the artist and Venice: he definitively goes to Rome to never return to the lagoons. His relationship with Venice is definitely a difficult one: he will continue to call and declare himself “Venetian architect”, but this could also be a way to differentiate himself in the Roman artistic environment, and this would agree with the position of block he always assumed. He could also define himself as a Venetian due to the undoubted links of culture and artistic experience, for his first introduction to the studies of architecture and perspective – he came from a family of builders and was the grandson of Matteo Lucchesi – for the teachings that he had come from artists Venetians who, as I think, he rediscovers or rather discovers only on his return to Venice, before abandoning it forever. But perhaps this “discovery” was none other than his encounter with Tiepolo. Biographers like to repeat that Piranesi would have been at his school, in his studio, working with him. We have no data to affirm it: however we have certain stylistic consonances typical of the years 1743-1744 that do not make us doubt that the encounter – of whatever kind – was decisive and decisive for the young Piranesi. There will be an opportunity to return and investigate this problem, but in the meantime it can be said that the fact should not surprise.

Tiepolo is the dominant figure of the months that Piranesi spends in Venice and the extraordinary skills of the painter must have fascinated him. There were undoubtedly differences between the two artists: but not in stature. And this must have facilitated the meeting. Only through Tiepolo, Piranesi must have glimpsed distant Renaissance worlds and beyond these an antiquity evoked with irony more than in its heroic values: perhaps more akin to Piranesi. But still this, a way of understanding each other, while other lagoon artists the young Piranesi must have felt strangers and far from his dreams and his burning passions. And, although enthusiastic about Palladio, he must have immediately understood how great the distance was between the master of the sixteenth century and the slavish Palladian followers of his own century. But this is not the place to dwell on this report. Interesting, however, is the difficulty that remains between him and Venice, on the other hand explicitly declared.

It was probably the eventful life of Piranesi’s children, especially Francesco, who, involved in political events, emigrated with his brother Pietro to Paris in 1799, which caused the loss or destruction of a very rich material, documents, letters, papers. According to Bianconi there was even an autobiography: everything seems to have been lost. So that each card, each surviving letter acquires an exceptional value and, together with his writings, must be held in high regard. Illuminating, in my opinion and especially as regards relations with Venice, is the letter cited by Biagi in summary (and here transcribed in the Documentation to D3J), sent in March 1778, (a few months before dying) to a sister living in Venice. In it, Piranesi takes stock of his own life and, frank as always, he lets himself go to considerations of extreme interest. He speaks of his works – at that time 18 Atlantic volumes – which “the Holy Father used to purchase from time to time to give them to the Princes who visited Rome, paying 200 scudi per copy”. He declares himself “son of Rome” because in Rome his talent had been known, because Rome with its monuments had inspired him, because he had been made a Knight, because he had made a fortune: he speaks of a substance of “60,000 scudi, part of which usefully invested and partly made up the capital, of which his workshop and museum are supplied ». He lashes out “against the pettiness and inertia of the Italians” of his century and praises the “profusions of the English nation”. It is at this point, after all this information, that his outburst becomes even more important, overcomes the biographical fact, penetrates into the essence of things and, for us, is worth more than entire volumes: “… If he were to choose a homeland he would prefer London to all the cities of the Universe ». And again: “… exiled from Venice, his homeland, for not having been able to obtain even a job … he will never return there again, especially since this city, although adorned with magnificent buildings and paintings, was not a theater capable of to graze the sublimity of his grandiose conceptions, as was Rome, and the other cities of southern Italy ». Extremely clear words and also consistent with the lines of behavior of his long-standing work – we are in 1778 – and which take on further interest in the comparison with the ideas, intentions and programs of many years before – 1743 – when he was taking his first steps just arrived in Rome.

Modern culture has undoubtedly accentuated the theoretical aspect of his works and writings. Above all, the example of the letter of dedication to Nicola Giobbe, placed at the head of the «First Part …», is valid, a document which, after being neglected for decades, now enjoys a rightly recognized favor. It may seem strange that such a key text has been overlooked or not taken into consideration as it deserved. Piranesi’s ideas – he was just twenty-three years old – are already expressed with great clarity and immediately make us understand what his interests in architecture are, his controversial position, his passion for Roman architecture, his abandonment of Venice, the clarity criticism of its lines of action. This text does not neglect any of the essential elements of Piranesian art, ideas and attitudes: the passion for Rome “Queen of the Cities” from the “august relics that still remain of the ancient Roman majesty and magnificence”; enthusiasm for architecture “the exact perfection of the architectural parts of the buildings, the rarity, or the immeasurable mass of marbles … or that vast expanse of space, which once occupied the Circuses, the Forums, or the ‘Imperiali Palagi … these talking ruins … »; the mention of his studies when he declares that before seeing them he had not been able to get an idea of the monuments, despite the fact that he kept “… always in front of his eyes” the drawings that “the immortal Palladio had made of them”; the distrust “neither being it hoped for an Architect of these times to be able to actually execute any”; the criticism of the Roman clients: “… the fault of those who should be patrons” … “and taking away [the architecture] from the will of those who possess the treasures and who make you believe they can talent to dispose of the operations of the same “; and therefore in pessimism, the only possibility of acting: “to explain one’s ideas with drawings” … “the art of drawing not only my inventions, but of still carving them in copper”. The explanation of Piranesi, “Venetian architect”, engraver, archaeologist, is all, sharp and clear, in this letter.

A lot of water has passed under the bridges – and not only under the Roman ones of Piranesi – since the first pioneers faced the enormous bulk of Piranesian work seventy and sixty years ago. A. Giesecke, A.M. Hind and H. Focillon were the first to initiate a long sequence of studies (and the bibliography at the end of this catalog is faithful testimony) which, recently, has found a renewed vitality. For completeness of philological investigation, critical penetration and extensive cultural information, the monograph and catalog of Focillon still remain valid, worthy of the critical intelligence and synthesis capacity of the great art historian. And rightly, when it was thought of preparing the Italian edition of his texts, in integrating the post-Focillon philological contributions with the novelties, a very opportune line was followed without abandoning the old structure of his catalog. This new edition (edited by M. Calvesi and A. Monferini) has undoubtedly given a beneficial shock to Piranesi studies in Italy, and not only in Italy, also because it served as a filter and reference point for what had been done on Piranesi. up to 1967. It is useless here to repeat the history of this work, which has already been scrupulously and intelligently examined in the two Introductions, by Calvesi in the monograph and by Monferini in the catalog: I would just like to mention a few more recent publications and studies. From the catalog of the Exhibition to the National

Chalcography and that of the French Academy in 1976, to the interventions of A. Robison in 1970 especially for the philological details; to the penetrating essays by Carlo Bertelli; to the Polemical Works of J. Wilton-Ely, and to the brilliant synthesis of R. Bacou; to the monograph by J. Scott, rich in information; the interventions by Elena Bassi on the Venetian cultural environment and by A. Gonzalez-Palacios on the furniture; to the catalogs of the Colnaghi Gallery, to those of T. Villa Salamon; to the subtle considerations of M. Tafuri on Piranesian ideology, up to the studies that appeared in this centenary year: the catalogs of the exhibitions in London, Washington and the Proceedings of the Conference “Piranèse et les Français” and the essay-monograph by J. Wilton Ely. They have been published in recent weeks and it has not always been time to take them into account in the preparation of this catalog. But not everything, on the other hand, I was able to include in my hasty list.

Two hundred years later this artist continues to interest, to be alive, to find correspondences even in the subtlest folds of our culture. Visiting and seeing this exhibition should also serve to get an idea and to find the clear line that unites his various works in a stylistic, cultural, ideological coherence, from the first timid «Vedutine» to the last «Vedute di Pest». Reality has it that his very first and last works are precisely “Vedute”. And it was precisely from this kind of engravings that he lived and this was his true professional activity that brought him fame and money. With other ideas he had left Venice, his true obsession being architecture, the debate on architecture, the utopia for architecture: that idea that he pursues linearly and constantly since the “First Part of Architectures and Perspectives” of 1743. And then he was only 23 years old!

But if the awareness of the importance and greatness of Piranesi is quite recent, it is perhaps the most prominent personality of our eighteenth century – it is also because it is an artist who has moved and who has operated ridge sites of different and opposite situations: the baroque world on one side, the neoclassical world on the other. Anticipating an interest in the ancient world, despite his anticipations, he remains alien to the poetics of neoclassicism, finding the humus of his vivid imagination in the thrust and tension that the formal Baroque world offered him and the moral and intellectual support in ideas of the Enlightenment.

In Piranesian work there are three components that can be identified: the vocation to architecture, the passion for archeology and the dedication to Vedutism. The interesting thing is to find out how these three components intersect, mix, and serve to accentuate themselves in their meeting for that final result which is the Piranesian work. All three of these components then find their point of reference – which in turn is the backbone of his creation – in that capacity for invention and in that baroque ignition that of his battle for architecture, of his archaeological research and its perspective layout always creates a poetic result, a “fact of art”.

The great means of expression, the vehicle that served to convey his visions, was etching, which he used with freedom and unscrupulousness, experimenting and continuously varying in the most various ways: unclassifiable for us. Almost every work presents novelty and surprise. The return several times on the same copper, already engraved, with reworking and repurposing and the varied use of inks (sometimes with the addition of sepia) gives surprising results of “color” and pictorial effects that suggest its Venetian roots: from black dark, to glossy black, to gray, to silver, sometimes obtaining refined, velvety tones. On the title page of the “Collection of some drawings by … Guercino” we were able to find a phrase that is emblematic: “Col sporcar si Trova”. It is the true motto of his poetry.

Giambattista Piranesi, Venetian architect, among the arcades Salcindio Tiseio, honorary member of the Society of Antiquaries of London, Member of the Academy of San Luca, Knight of the Golden Speron, son of Rome, died on 9 November 1778, surrounded by his family, refusing medical treatment, asking once again to read Tito Livio, to review his drawings, his etchings, his engraved branches.

Two hundred years later we remember him isolated and solitary in his greatness, like an ancient hero out of his true time; of antiquity now inert he has been able to transmit an image that is still alive and throbbing; archeology has given us a science of precise information and not of empty romanticism; of architecture has identified in advance the terms of a crisis and has perceived in advance its dramatic value.

San Giorgio Maggiore, August 1978

Alessandro BETTAGNO

Alessandro Bettagno (1919-2004), Venetian art historian, exhibition curator, university professor, was the last exponent of the glorious generation of great post-war scholars.

SEE THE GALLERY OF ALL PIRANESI PRINTS