The IFC file format and BIM interoperability

The IFC format is the standard that guarantees interoperability within BIM projects

The IFC format was created to be open source, neutral and independent from software houses, in order to guarantee interoperability between professionals in the construction sector, without restrictions related to the file format of the programs in use by each one.

The international organization buildingSMART is responsible for the birth of the IFC (Industry Foundation Classes) format. Once known as IAI (International Alliance for Interoperability), buildingSMART was born in 1994, today it branches into various national branches called Chapters, such as IBIMI (Institute for Building Information Italy) and buildingSMART Italy. It is to all intents and purposes one of the main benchmarks for open digital standards. If you still don’t have clear ideas about what BIM and OpenBIM are, starting from the IBIMI home page (videos included) may be a good idea.

The IFC file format was born and spread to respond to a series of intentions that cannot find adequate answers in the proprietary file formats of the various applications, nor in the most common CAD file formats that do not contain information associated with geometric elements, i.e. that are not BIM. IFC not only guarantees an open and internationally recognized mode of interchange, but also wants to be useful for extrapolating different data depending on the discipline involved in a given point of the design or management process, as well as a secure way of archiving data based on a shared classification of terms that makes consultation easier over time, which is also very important for the facility management of the building during its life cycle.

IFC format files are the best choice for exchanging BIM files that are good for everyone

The IFC was created to constitute a sort of common base that everyone can draw on to communicate with each other, not to have a file like the one in a proprietary format, only with a different extension. The proprietary formats are the best thing for a group that uses the same program and perhaps works on the network on the same file, while the IFC serves to guarantee the most diverse uses of the model regardless of the software in use, including archiving and view with one of the various viewers available.

Speaking of IFC viewers, many software houses offer free ones and there are also independent and open source ones. In addition to the simple display and any other features, they have another advantage, that of acting in some way as a “judge” when two different software cannot speak well via IFC, ie when you export an IFC file from a software and someone else must import with another program. If in import you do not find what you expect, there are two cases: if the “judge” viewer reads the file correctly, it is very likely that the problem is in the import, because it is evident that the exported IFC file is good; if, on the other hand, things are not right on the viewer, it will be necessary to review the export settings. For obvious reasons it is useful to choose a viewer not produced by one of the two software houses of the programs involved in the dispute, or better still an independent viewer.

For a nice list of free IFC viewers you can check out ifcwiki, but there are others as well. Two that deserve to be taken into consideration, if only because they are cross-platform (Mac and Win), are Solibri Anywhere and OpenIfcViewer from Open Design Alliance.

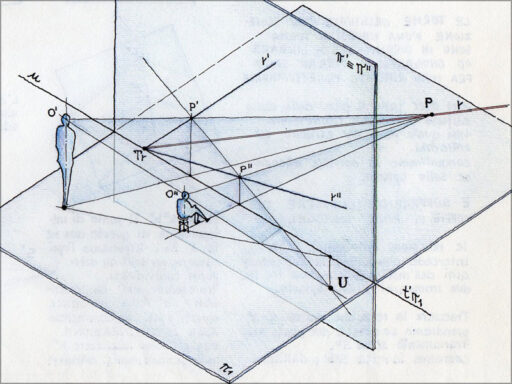

How to use the IFC file: editable and reference models

The IFC format was created for interchange, therefore more as a reference model for coordination, rather than as an editable model for continuous changes open-modify-save-close (which is still possible), therefore in principle it must be imported, rather than open. Then at the end of your part of the work you will export another one that can be imported again into the BIM authoring program, the one that manages the federated model, that is, it contains all the contributions of all the professionals involved. All this has obvious implications on the responsibility of whoever does what, with all the related regulatory references.

It is clear that the installer can find it very convenient to have the architectural and structural project to work on it, because it is not necessary to drill the beams to pass the systems. But he cannot even think of modifying the structuralist’s project as it suits him best and perhaps even without the engineer knowing that the structure has calculated and signed it. So the general idea is that everything is available to everyone for consultation and use as a reference model, but everyone can get their hands on and modify only what they are responsible for, coordinating with what they develop, or have developed the others.

But then doesn’t it continue to exchange classic CAD files all the same? No, because they have no information associated with three-dimensional elements, they are only 2D drawings or 3D models, so if we talk about BIM, they are of little use. When you swap and then import a 3D CAD file you get a series of geometric elements (but it could also be a single block) that are not distinct from each other in functional elements (walls, pillars, windows, furniture, etc.), not they have a precise location in space (a building floor, functional area, etc.) and have no other specific associated information (materials, stratigraphy, transmittance, price, etc.).

In addition, with the IFC you can choose to filter the elements of the project before exporting it for another professional, in order to provide him with a leaner and easier to use model. For example, in passing an architectural project to the installer, it may be useful not to include a large part of the furniture and for the openings the drilling may be enough, without other details regarding the frame (perhaps it is useful to point out the sliding doors in the thickness of the wall) . In the same way, the properties and attributes associated with the objects can be filtered, for example not all the professionals involved are interested in knowing the fire resistance class of the doors, or the brand, model, price of the sanitary ware, or the procedural textures. associated with the walls that will be flaunted in the renderings.

Knowing the IFC format helps to structure the project

A BIM model is such if it is composed of elements that have some characteristics suitable for describing what they are used for, how they relate to other elements, what shape they have, how they are uniquely identified and possibly if they have other useful information associated with them . All this information will be found in the IFC file, with obvious practical implications. So even conceiving the project from the beginning with this type of classification in mind can be useful, perhaps a little laborious especially at the beginning, but it is a game that is worth the candle, both in the development of the project (even more so if it involves more professionals), as well as in the operation and maintenance of the building.

To give a practical example and clarify things better, we can start from a very simple case and consequently use the same logic for elements that involve greater complexity, such as multilayer walls, structural elements, etc. Two identical street lamps a few meters away in a park must have at least one code that clarifies their specific identity, so if a lamp goes out, the maintenance technician on duty can easily identify the right one, because it has been reported to him and is indicated precisely on the map of the park (which he could view on a tablet).

For the designer, if they are identifiable one by one, then they can also be “counted”, so the calculation of how many street lamps of that type will be needed in the park is an automatic function of the design software and if the price can also be entered in the object , the total amount is received.

The street lamp has a relationship with the ground of the park, it rests on it, it does not float in the air (just as doors and windows exist only within a wall element), it has a support height and therefore belongs to a given floor of the project (it is not displayed on the third floor above ground, nor in the second basement), it can be part of a certain category or functional area and can contain information, such as the type of lamp it is fitted with. At this point, the maintenance technician also knows what to bring with him from the moment of the fault signal and maybe he can restore the right lamp by climbing only once.

Certainly the lamp has a 3D geometry and also a 2D representation more or less refined according to the needs, but sufficient to identify it visually, or to make it look pretty good in the rendering. The casing is enough, not all the internal components that are not seen are needed, while the manufacturer and model can be included in the information associated with the object and refer to a specific technical sheet for assembly and maintenance. The project of the lamp post in every single component, on the other hand, concerns the company that produces it, not the designer of the park, because even in BIM at a certain point it is necessary to set limits.