The landscape is the product…

Landscape is memory - Landscape is a repository of history

The landscape is the historical product of culture and man’s work on nature

…First of all, we need to define the object around which we think: the landscape. I therefore want to remember that the landscape is the historical product of culture and man’s work on nature.

In the landscape, in the form of the territory as it appears to us, nature and history are integrated variously in the various parts of the planet. They thus form different types of landscape (natural, agricultural, urban), each of which is characterized by different genesis, characters, meanings, usefulness, and problems. It is precisely their genesis, characterized by the synthesis between event and site, which therefore defines the identity of the places: a constitutive element of the very identity of the communities, national and local, that those places inhabit. Product of history, and identity of places and communities: these are the attributes of the landscape that above all interest me.

I am not proposing a particular interpretation of the landscape here. If the accentuation of the role of history in the formation of the landscape (and therefore in the understanding of its values) is typical of some important schools of thought (from Emilio Sereni to Piero Bevilacqua, to remain in Italy), in the Italian and European cultural events the landscape has been the subject of different interpretations: from the aesthetic to the historicist, from the “archeology of the territory” to the “ecology of the landscape”. However, I do not believe that one should choose between one or the other interpretation. This is not the expression of antithetical positions, each of which is opposed to the others, but the highlighting of different points of view, each of which emphasizes one aspect of the landscape, revealing its richness and complexity. The landscape, the history, the man.

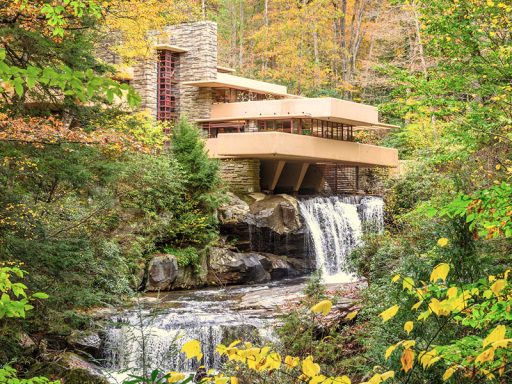

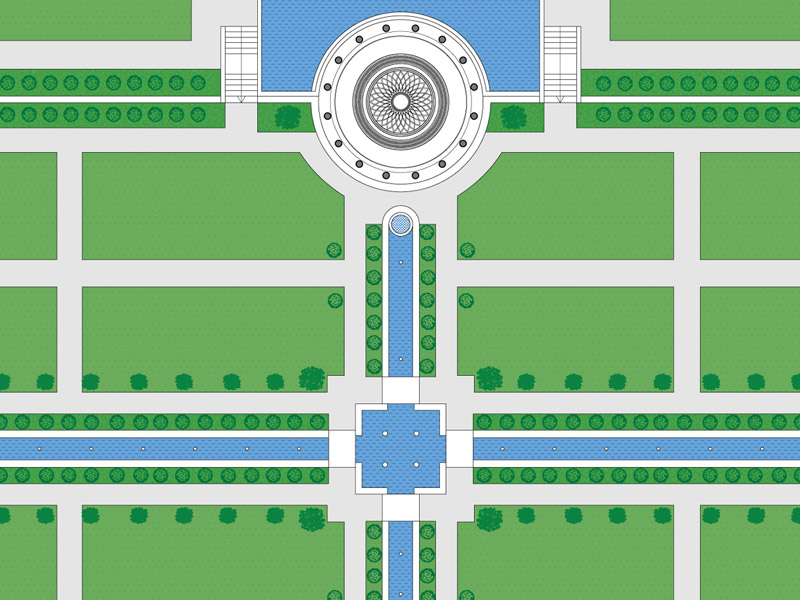

Underlining, as it seems right to do, the role of history in the formation of the landscape (and therefore of its value) means placing emphasis on the role of man. It is therefore necessary to recognize that man’s intervention on nature has had and has different signs. Sometimes (in certain eras, in certain societies, in certain places) a positive role: it has built landscapes (urban, agricultural, even natural) to which we recognize today the teaching value and aesthetic value: with simple maintenance, or with formation of new agricultural landscapes, or with the creation of works integrated into the pre-existing landscape, man has added value to the shape of the Earth.

But other times (with neglect and abandonment, with the elimination of the signs of the past in the name of immediate profit, with insane artificialization) it has subtracted value and destroyed the cultural and historical heritage constituted by the landscape, it has reduced the wealth of human civilization. We must then ask ourselves a disturbing question.

Is today’s society, the culture it expresses, able to place itself in relation to nature and the construction of the landscape in the same way in which the men whose products we admire today have placed themselves, and in which we recognize an essential component of our identity? Urban and hyper-urban landscapes, the devastation of the countryside, the destruction of natural environments, created in Italy in the last half century, leave no doubts in this regard, and invite the utmost attention in the face of the temptation to “let the guard down” of the action of protection.

Utility of the landscape

To reverse the trend, to learn anew to govern nature without denying it, the protection of the landscape must become a social priority. For this to happen, it is necessary to make it clear to everyone what are the reasons why it is socially necessary to protect and enrich the quality of the landscape (landscapes). Why, in short, is the landscape useful?

First, the landscape is memory. The landscape is a repository of history. In it is represented and witnessed our past, the past of our civilization. It is therefore the foundation of the identity of the different communities that inhabit the planet (from national to local). It is useful (to us, and to future generations) because it is an irreplaceable resource of civilization, it is the vital material that feeds the future. This would be enough to understand how a society that wants to exist must preserve the landscape as its own primary resource.

But the landscape is also an economic resource. Increasingly, in the modern economy, sectors linked to the production of “intangible assets” tend to increase their weight (until they become dominant), including those related to recreation and physical well-being, tourism, knowledge and to aesthetic enjoyment they take on increasing importance. In many areas of Italy (and Europe) the quality landscape is a place and condition for “niche” food and wine productions, characterized by quality and identity, fundamental both for the economic and social development of the areas involved and for conservation. of universal values.

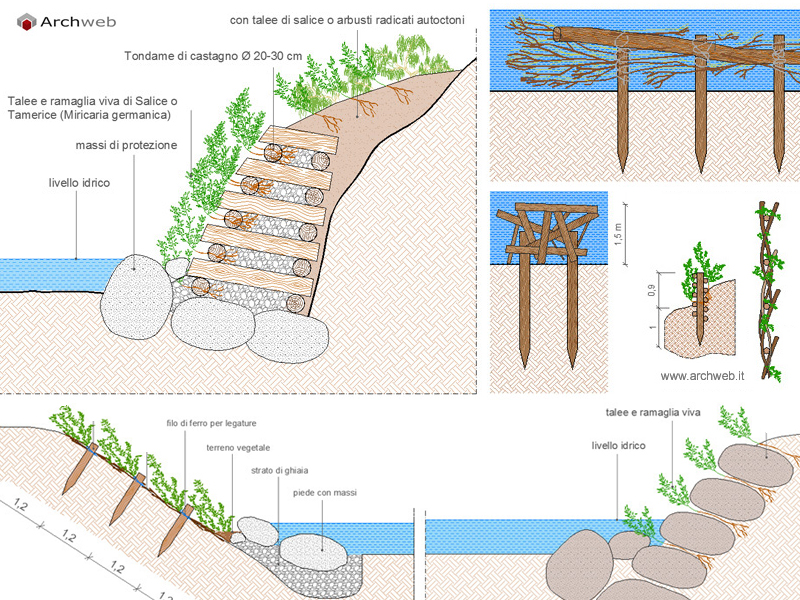

Regarding the economic role of the landscape in the coming decades, the importance that an action of soil maintenance, reduction of the risks and costs of environmental degradation, of start-up may have for the development of employment in many Italian regions should not be overlooked. an environmental protection action. It involves restoring and maintaining natural environments destroyed by human neglect (and threatening for survival in the areas downstream of degradation), or environments characterized by an assiduous relationship of construction of the agricultural landscape.

The quality of life is also linked to the quality of the landscape: The beauty of the views, the harmony of the places where her life takes place are essential for the well-being of women and men, children and the elderly. In the era of globalization, competition between regions and cities increasingly assumes the quality of the environment (as a component of the quality of life) as an economic value to be put into play in “urban marketing“. This poses, once again, the economic need to improve the quality of the landscape even where (as in the urban suburbs) one has not been able to create new qualities, but only to destroy the pre-existing ones.

Addresses for planning

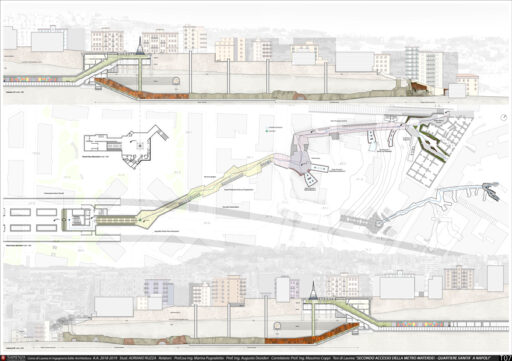

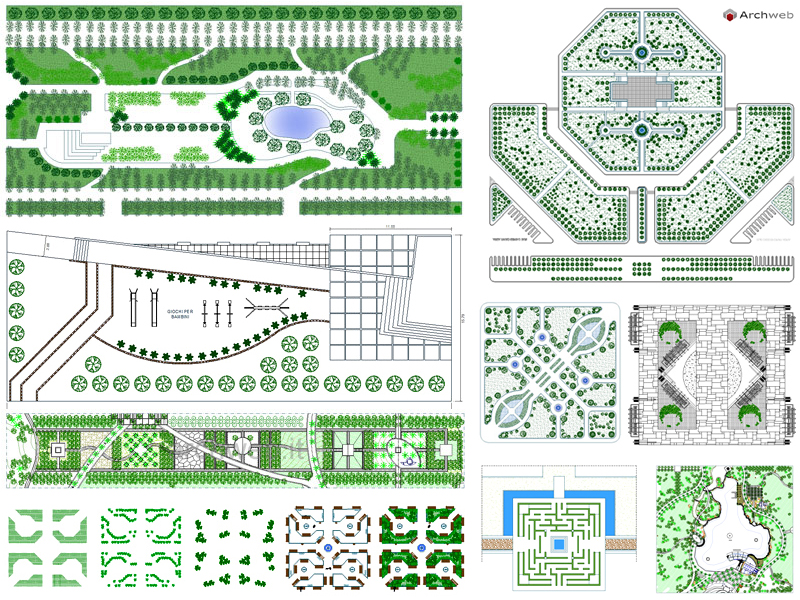

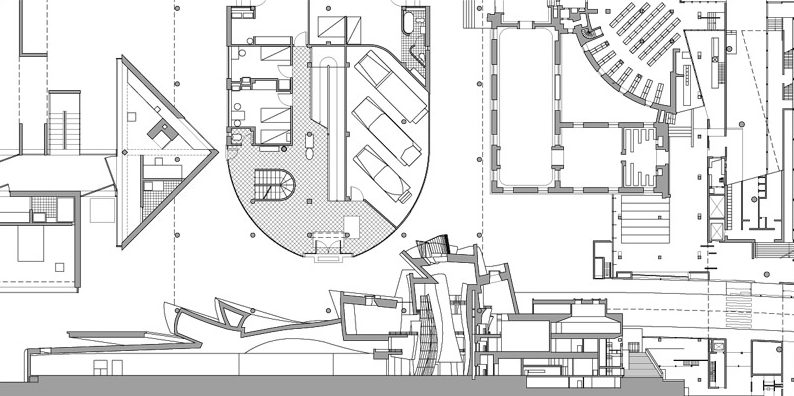

The primary objective is to give full effect to the protection and enjoyment of the landscape assets (of those existing and those to be built) by present and future generations. Territorial and urban planning, as a set of methods and tools aimed at ensuring consistency in the transformations of the territory by ensuring transparency and participation in the decision-making process, is the scope within which this objective can be achieved.

From this point of view, it seems particularly significant to me the way in which Law 431/1985 (the so-called Galasso Law) laid the foundations for innovating the planning system. The law was only partially implemented, and its implementation was often a circumvention of its aims. But the experience of implementing that law (where there has been positive implementation) leads us to underline, and to propose some particularly significant guidelines.

I will state them in very succinct terms.

The “careful consideration of landscape and environmental values“, which law 431 requires of ordinary planning to be effective, must become a constant in ordinary territorial and urban planning, at all levels: national, regional, provincial, municipal.

More precisely, the first phase of planning must consist of the assiduous recognition of the natural and historical qualities of the territory, as attempted in the experience of the Emilia Romagna Region of 1985-86 and as prescribed, in more or less clear ways. , the new urban planning laws of Tuscany and Liguria.

The recognition of the quality of the territory must preceptively lead to the identification of the admissible physical transformations and uses compatible with the characteristics of each unit of space, as a non-negotiable condition for any decision on the transformation to be promoted or allowed;

Active protection of the landscape requires that all available tools be integrated into the planning process: sector policies and actions, financial incentives, participation in national and supranational programs and projects, the use of private entrepreneurship. These tools must not be used in contrast to planning or as an alternative to it, but – indeed – as its tools.

Underlining the usefulness of planning (as it seems essential to me) means recognizing the partiality, and therefore the insufficiency of the passive protection constituted by the protection constraints). But I believe that the cultural and moral climate we are experiencing (the Eighties never end!) At the same time require us to reaffirm its usefulness. The constraints, although not sufficient, are useful in two respects. In the first place, the constraint is necessary as a temporary defense, waiting for planning to allow the articulation of protection policies, both active and passive. Secondly, because (as the experience of law 431/1985 demonstrates) the constraint acts instrumentally as a solicitation to planning, and therefore to the possibility of a more complete protection and use of the landscape assets that guarantees their conservation.

Subsidiarity and understanding

One last point I would like to touch briefly. The protection and enhancement of the landscape expresses a plurality of collective interests: from national to local ones. It is necessary to avoid both the risk of paralyzing conflict and that of the denial of one or the other of the interests involved.

The principle of subsidiarity is the criterion that can be used to identify who is responsible for the choice in relation to the objects and aspects on which it is necessary to decide. It is, of course, if it is taken in its correct meaning, the one developed in recent European culture. Not the principle of subsidiarity understood as “all power on the periphery”, but as recognition of the fact that for every decision there is a fair level at which that decision can be taken effectively. But the official text holds:

In fields which do not fall within its exclusive competence, the Community intervenes, in accordance with the principle of subsidiarity, only if, and to the extent, the objectives of the proposed actions cannot be sufficiently achieved by the Member States and, due to their scale or of their effects, can be better achieved by the Community [1].

It is really difficult to think that the landscape, being a fundamental element for the definition of national identity, does not fully fall within the responsibilities (and competences) of the state, since it is a question that arises on a national scale.

But if the central bodies of the state have the responsibility for the protection action, they also have that of promoting the competition of powers in the protection action. If the primary responsibility in matters of landscape rests with the state, even the levels of regional and local government are entitled (I believe I have reasoned this sufficiently) to compete with it in the action of identification, definition, protection.

How can competition be exercised in the field of spatial planning and landscape protection? Here too there is a principle, and an institute already introduced in our legal system, which can help. It is the principle according to which planning tools, where they govern state assets in terms such as to affect their finalization, can only become effective after “agreement” with the state itself.

This principle, moreover, was recently introduced in the legal system, albeit limited to provincial planning, by article 57 of legislative decree 112/1998, which establishes that:

the region, with regional law, provides that the provincial territorial coordination plan […] assumes the value and effects of the protection plans in the sectors of nature protection, environmental protection, water and soil protection and the protection of natural beauties, provided that the definition of the relative provisions takes place in the form of agreements between the province and the competent administrations, including state administrations.

As the Polis association proposes, this regulatory text can constitute, can be extended beyond its specific context, and constitute a model on the basis of which to fully address the issue. Moreover, it is a model that has already been proposed several times and applied in concrete experiences of territorial governance and can give rise, as has been observed, to useful simplifications and streamlining of procedures. What is in everyone’s interest.

Author: Edoardo Salzano

[1] Trattato di Maastricht, art.3B.

Article for “Gazzetta Ambiente”, Venice, 2 July 1999.

The article was taken from the website: www.eddyburg.it