Wooden buildings against CO2

Wooden buildings will save the cities of the future

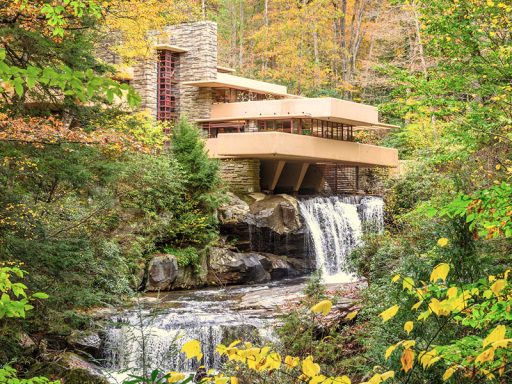

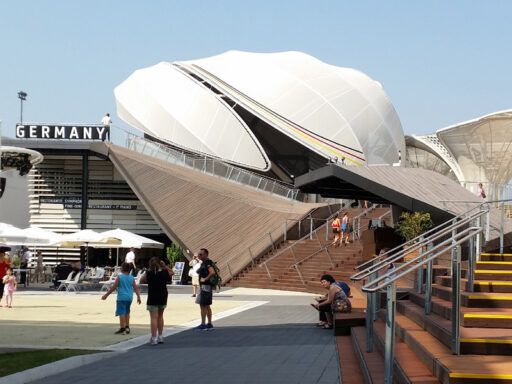

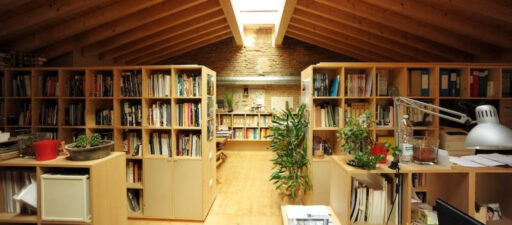

As with snowflakes, individuals and other products of Nature, no two perfectly identical pieces of wood can be found. Perhaps it is also for this peculiarity that wooden buildings usually give us a greater sensation of warmth, make us feel more in tune with the environment, as if we recognized in them something alive and familiar that tells us of an intrinsic relationship between nature and the built environment.

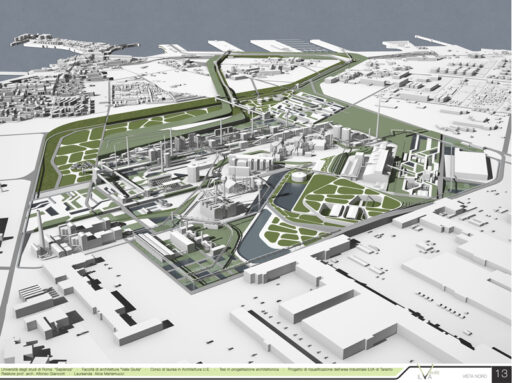

The structure of the buildings of the future will be made of the same material as prehistoric stilt houses: wood. New skyscrapers and large wooden residential buildings will help reduce greenhouse gas emissions, meeting the housing demand of metropolises over the next twenty years.

In Italy we are used to thinking of wooden houses in terms of huts, cottages, bungalows or little more. However, low buildings, usually in a bucolic environment or which in any case have nothing to do with the urban context. Or we use wood for roofing and laminate for sports halls, swimming pools and other large covered surfaces. Otherwise, the residential neighborhoods of single-family houses in the United States, the ones we see in the films, may come to mind. But we are always outside the city and with a large consumption of land.

Italians are fond of brick and in large cities buildings have multiple floors, so they could not be built with a wooden structure.

The Canadian architect Michael Green explained during a TED Talks in 2013 that it is possible, offering a vision that is as futuristic as it is simple and supported by data that leaves little room for interpretation. Let’s try to take up his speech and bring it into Italian reality.

About half of the world’s population lives in cities today and it is expected that this share will rise to 75% in the next 20 years.

It is estimated that 3 billion people around the world will need a new home in the next 20 years, most likely in the city, or rather in those metropolises which already host 1 billion people in their poorest and most degraded neighbourhoods, plus millions more homeless. Considering that urban space will be increasingly smaller, more and more expensive and that it will be necessary to somehow find homes for so many people, it is unlikely that the buildings will subside, so they will not be wooden buildings.

Not bad, we have steel, concrete and bricks, we can build as we have done up to now.

One of the problems is that the production of these materials involves a high emission of carbon dioxide, partly due to the passage through an oven at a more or less high temperature. Already today, steel and cement contribute 8% to the production of greenhouse gases.

If we think about the necessary reduction of carbon dioxide and the rise in temperature due to greenhouse gases, the urban population increase scenario described appears decidedly gloomy. Already, buildings and their normal functioning are responsible for around half of the carbon dioxide produced, it is clear that being able to limit their impact has great environmental value.

Not that the situation is rosier on the transport front, but when we think about pollution it is easier for us to associate it with cars than with houses and this is already a good guarantee so that we don’t forget that urban traffic is a problem. Perhaps for buildings this type of association is not so immediate.

We know that heating civil buildings has a significant impact on pollution.

Anche il famoso bonus del 110% punta a ridurre consumi ed emissioni, in particolare nelle abitazioni costruite negli anni del boom edilizio e che oggi rappresentano una parte consistente del nostro patrimonio residenziale. Tuttavia è meno frequente sentir parlare del consumo energetico che interessa il ciclo di produzione degli edifici e dei materiali da costruzione. Anche se gli edifici non si smaltiscono con la frequenza degli elettrodomestici, bisogna comunque ragionare sul loro intero ciclo di vita e sul consumo energetico che questo comporta. Per questo è importante partire dalla produzione dei materiali, dall’energia, dalle fonti utilizzate per ricavarla e dalle emissioni che già questa comporta.

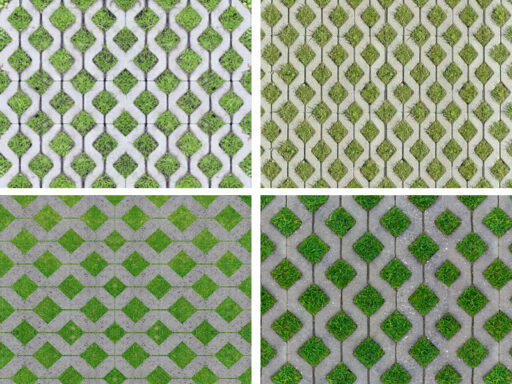

Wood is the only building material that is produced using the sun’s energy.

The tree uses the energy of the sun and the resources of the soil to grow, at the same time releasing oxygen and absorbing carbon dioxide. The natural epilogue of the tree’s life involves it dying, drying out, falling and rotting, or in some cases burning, still returning carbon dioxide to the atmosphere and soil. However, if you cut the tree when it reaches full growth and make beams from it which you then install in a house, the carbon dioxide is frozen inside them, it is not dispersed into the environment and, like Palladian trusses, may remain there for several centuries.

One cubic meter of wood can trap one ton of CO2.

Perhaps wood will not be the magic wand, but it could rightfully become part of the solution, because it can reduce emissions, lock in CO2 for years and also produce oxygen as it develops, especially during the growth phase of the tree, when the Forest is still young.

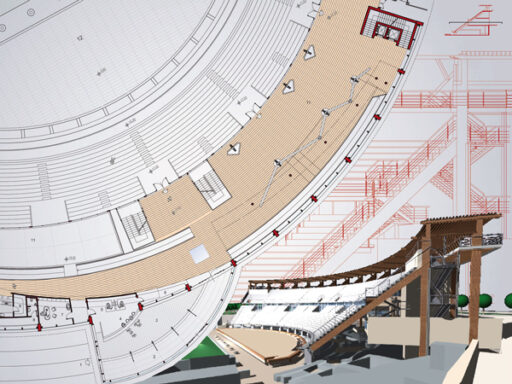

Wooden buildings could represent a step in mitigating the multifactorial and multidimensional problem of air pollution. For this reason Michael Green and engineer Erik Karsh thought of creating 30-storey wooden buildings, using a technology they called Mass Timber Panels.

Who knows if any research has ever highlighted what meanings are attributed to wood in proverbs and popular culture, already the fact that villages were putting themselves to “fire and sword” suggests that steel is faring worse.

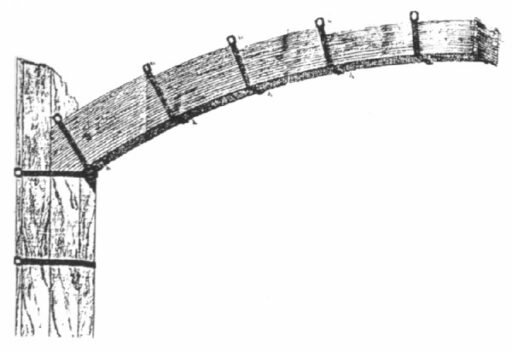

These are large panels of various thicknesses generated by young trees, not of large size, nor of particular value.

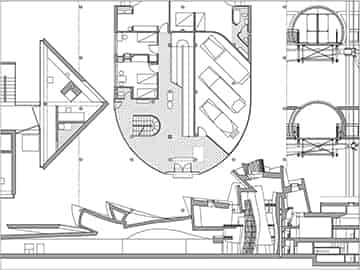

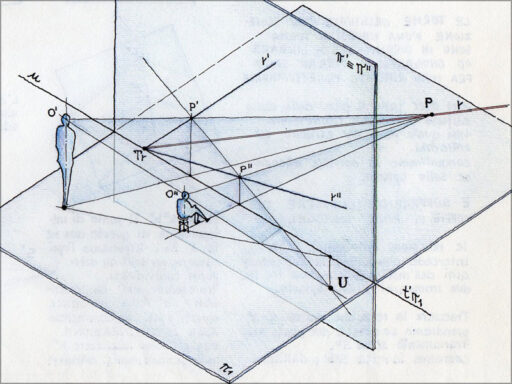

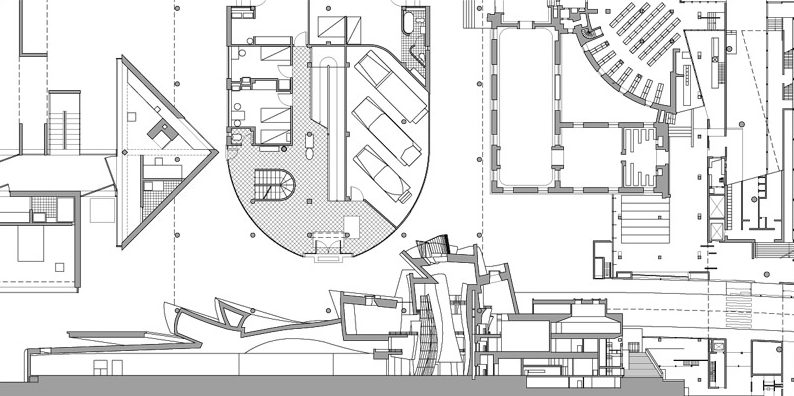

During the TED, the construction system is explained by referring to Lego, talking about the bricks we all know and comparing the wooden panels to larger Lego pieces. These panels of approximately 50 m2 constitute the system created by the Canadian architect which takes the name of FFTT and is a Creative Commons solution (therefore not covered by an exclusive patent, but can be used freely) to assemble the structure of buildings in a very flexible and with great speed of execution, as shown by the animation presented during the conference.

The project is designed for a 100 meter high building in Vancouver, a city that also boasts a fair seismic risk, but the designer declares it to be suitable for any context and stylistic solution.

Green’s presentation continues by dispelling the most common doubts related to wooden constructions, such as the risk of fire and the cutting of the necessary trees. The most interesting thing is precisely linked to the need to have trees, which would lead to re-evaluating this crop, investing in young forests and cutting them consciously, putting a stop to the deforestation for agricultural purposes which afflicts the Amazon for example.

The carbon footprint of this type of construction technology is decidedly advantageous compared to traditional ones, especially considering the future increase in population and urban residence.

In the end, the biggest problem is, as often happens, that of a change in mentality, because it is a truly new technology for building skyscrapers which have always used steel and reinforced concrete.

Design, technology, the availability of wood and the possible development of the supply chain compared to the mentality and common feeling are simple things. Wooden-framed buildings are rising, just as steel skyscrapers were rising a century ago. There are already several wooden constructions 30-35 meters high scattered around the world, up to the 85.4 meters of the Mjøstårnet giant in Norway, passing through the 53 of the Tall Wood Residence in Vancouver, as Michael Green had promised.

Where are we in Italy with wooden buildings? How much can we make Michael Green’s innovative drive our own?

It may be that a country with almost zero population growth like Italy will not be at the top of the list of countries with the high rate of urbanization predicted by Green in the next 20 years, and perhaps not even the rate of urbanization will be so disastrous. China, India and Brazil will probably take the lion’s share.

Although the Vaia storm that hit the Dolomites in 2018 provided a certain surplus of material, Italy certainly does not boast the forests of Canada and is not even famous for its quantity of skyscrapers, which are rarely used for purely residential purposes. This does not mean that we will still be affected by these wide-ranging dynamics.

Even if this is not the place to discuss technical-regulatory topics, it should be considered that the adoption of wood for structural purposes in our country is rather recent. About a decade has passed since the technical standards of 2008 which were the first to place this arrow in the quiver of the designer who wants to think of complex housing structures without making use of conventional solutions.

These standards, which allow the creation of complex wooden buildings, derive from various factors, including an increasingly conscious push towards bio-architecture and the need for energy containment, but also from the practical needs linked to the earthquakes in L’Aquila and Molise which required to quickly create buildings that are safe from a seismic point of view.

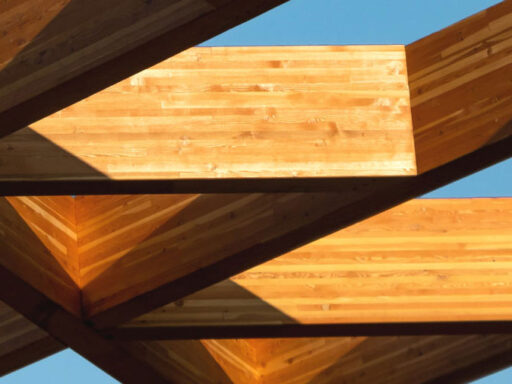

It is in this context that in the last 10 years there has been a big push towards the use of XLAM (or CLT) for wooden residential buildings.

Also in this case these are wooden panel structures, i.e. solid elements, which can “familiarise” you with our construction tradition made of brick walls. Assimilating the adoption of the wooden frame construction systems typical of the Anglo-Saxon world would not be as easy.

At the moment we haven’t gone as far yet, certainly not as much as Michael Green suggested in 2017, but at least we are proceeding to dissolve the “wooden house – same – mountain cabin” equation.

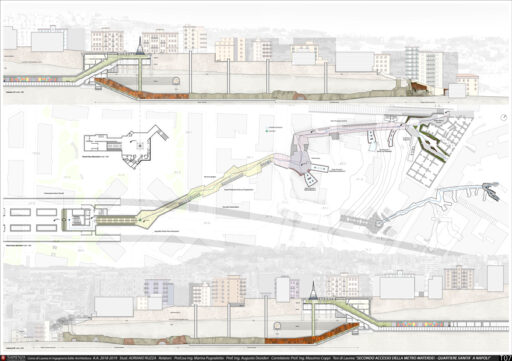

The reconstruction for L’Aquila required rapid completion times and this pushed towards the use of wooden structures with which residential buildings of up to four floors and a seven-storey hotel were built, the Alexander Residence in Roccaraso, completed in 2012.

The 2019 “Wooden Houses and Buildings Report” reports an increase in the sector of 2.3% and highlights the growth of this industrial sector especially in Lombardy, Veneto and Emilia Romagna, with a promising expansion towards Tuscany, Lazio and Marche.

One of the most comforting signals also in terms of exports comes from XLAM Dolomiti of Castelnuovo (TN) which in recent years has also installed its panels in a 5-storey wooden building on the University Campus of Melbourne, in addition to the many creations in Italy. Leafing through its catalog it is interesting to see how the short sheets of each creation report the tons of CO2 saved and how this material lends itself, especially by virtue of its lightness, to elevations.

In our small way, even if we fly low, we are moving towards a greater use of wooden structural solutions for construction, without clear distinctions both in terms of type and intended use. Considering all the advantages that wood can bring us and the technological-constructive level now achieved, it is difficult not to want to encourage its development.

SOURCES

TED Ideas worth spreading – Michael Green | TED 2013 | Why we should build wooden skycrapers

Multi-storey wooden buildings with CLT load-bearing panels | Agostino Presutti, Pierluigi Evangelista | 2014 Dario Flaccovio Editore

XLAM DOLOMITI construction catalog 2019 | Building with Timber

The important performances of Xlam Dolomiti in Italy and around the world | impresadilinews.it

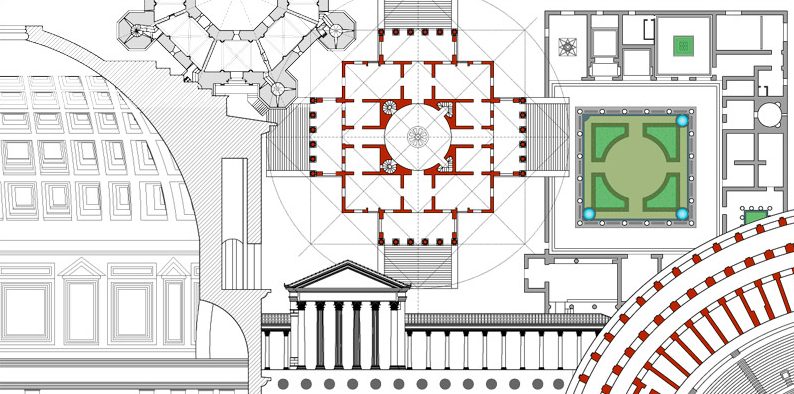

Cover image: IZM, Dornbirn by woodskyscrapers.org